This is the report that JustUs initially submitted to Richard Fuller MP in March 2017, then Mohammad Yasin MP in August 2017, then Mayor Dave Hodgson in December 2017 and was ultimately passed on Cllr Anthony Forth, who is portfolio holder for Adult Services. The report was left unchanged from the version submitted to Mohammad Yasin, which is why it refers to him throughout.

We have included the reponse in a separate tab.

In order to guarantee confidentiality, some case histories have been anonymised further and some have been removed entirely from this version of the report.

To make the report more accessible, the layout has been changed and photos have been added.

Domestic Abuse and Homelessness: Bedford Borough Council’s repeated failures to discharge its homelessness duties lawfully to victims of domestic abuse.

Contents

Introduction

Section A: Case Studies

Section B: Conclusions

Section C: Recommendations

Section D: Relevant information from the law and local policies

Introduction

The focus of this report is Bedford Borough Council’s discharge of its statutory homelessness duties to homeless people affected by domestic abuse. Bedford Borough Council discharges it duties primarily through its Housing Options Team. This report has been created in response to ongoing concerns that JustUs workers have following their clients’ experience of the Housing Options Service.

It is important to state that we have not set out to focus our services on victims of domestic abuse, rather it simply appears that many people who experience homelessness do so because of domestic abuse.

At the time of writing (June 2017, JustUs caseworkers have supported more than 52 homeless individuals from 37 households, across several local authorities (but mostly Bedford Borough), the vast majority of whom have been supported into safe, independent accommodation. Of those 52 individuals, domestic abuse was a significant factor in 20 of them becoming homeless.

Many of the concerns raised in this report are of a serious nature and detail failures that have caused significant injustice to victims of domestic abuse, including children. It is the primary intention of this report to bring these concerns to the attention of Mr Yasin MP so that some form of independent investigation can take place and so that any identified failures can be properly rectified. By highlighting these failures, it is our hope that when a homeless person affected by domestic abuse approaches the Council for assistance, they shall be treated lawfully and with dignity, and that the Housing Options Team will be effectively trained and resourced to make the most of the opportunity to minimise the harm that people suffer because of such abuse, and to maximise the chance of their recovery.

The detrimental effects of domestic abuse on families is incalculable, both in the short and longer terms, to the point that these effects become barriers for many victims to enjoy a basic standard of life, and subsequent opportunity to contribute to and engage with society that should be open to all. This view is based on research published by a wide variety of sources from many organisations, including numerous Government white papers (e.g. https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/violence-against-women-and-girls, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/domestic-violence-and-abuse). Theresa May has recently spoken about the issue and stated that ‘Domestic violence and abuse is a life shattering and absolutely abhorrent crime… There are thousands of people who are suffering at the hands of abusers - often isolated, and unaware of the options and support available to them to end it.’ (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-39011224). We hope that Bedford Borough Council’s Housing Options Service can operate with this in mind.

Sadly, it seems, from our experience, that the more vulnerable the person is, the easier it is for the Council to discharge their duty to them unlawfully, and the less likely it is that that person will have the capacity to seek justice without easy access to legal support.

JustUs has already brought many of the concerns to the attention of the Council through the Council’s complaints policy (which have all been at least partially upheld) and to the Adult Services Health and Social Care Scrutiny Committee, but it seems the cases are still being treated as isolated failings, rather than indicators of systemic issues affecting a much larger number of people.

This report comprises of three sections; firstly, anonymised case study accounts of individuals who JustUs are aware have been failed by the Housing Options Service, secondly our conclusions with some recommendations on how, from our experience, we believe the service could be improved and thirdly an outline of relevant law and policy.

In particular, the case studies demonstrate clear examples of individual failings on the Council’s part and indicate wider concerns that we believe warrants further independent scrutiny of the Housing Options Service’s current practice. Whilst it is certainly unpalatable to put it in these terms, the failings may well meet the criteria of institutional abuse, acts of omission and misfeasance in a public office where staff are knowingly discharging duties to homeless people at risk of domestic abuse unlawfully.

We believe that an effective Housing Options Service is likely to bring huge savings across the Council, both in the immediate future and in the longer term (not to mention savings made to the police, prison, probation, health and homelessness sectors). In our work, we have dealt with various Bedford Borough Council’s social care teams who are under similar financial pressures as Housing Options no doubt is. However, we have never had cause for concern in how social care teams deal with vulnerable people and see no reason why it is not possible for Housing Options to operate to similar standards of professional practice.

We live in a time when institutional failings of statutory services leading to abuse and neglect of vulnerable people have been prominent in the public’s consciousness. The Jay report, published in response to the Rotherham Abuse Scandal, echoed findings in other cases which identified that senior staff in statutory organisations knew, or should have known, that abuse was happening but failed to take necessary action to respond. In the light of our experiences with Bedford Borough Housing Options Service, we seek the prevention of similar organisational mechanisms occurring which defend failures rather than constructively respond to them.

The case studies have been anonymised.

Section A: Case Studies

The following accounts have been anonymised, but the substance of each case has not been changed.

Ellie

Ellie’s case acted as the catalyst to set JustUs up, so this incident occurred just before JustUs was set up in February 2014.

Ellie lived with the father of her four-year-old daughter and was 7 months pregnant. She had some care and support needs. Her partner was frequently physically and psychologically abusive. On one occasion, he broke her collar bone and she subsequently left her home with her son and stayed with a friend, sleeping on the sofa with her son sleeping on an airbed on the lounge floor.

Ellie approached the Council and informed Housing Options that she was homeless and in need of assistance. The officer did not accept her request for assistance as an approach under s.184 as required by Law. The officer did try to arrange for Ellie to be accommodated in a refuge in Peterborough, but this would not have been a lawful discharge of the Council’s duty. Ellie had no obvious way of travelling to and from the refuge (the route cost approximately £20 each way on public transport) and would have been away from all her social and professional support network in Bedford. She also did not want to disrupt her daughter’s attendance at her pre-school where she had settled in well and was receiving good support. The officer gave her literally 10 minutes to make the decision and she decided that it was not in any way workable for her and her daughter due to her being about to give birth, the cost of travel and distance from support network so she returned to her friend’s flat. There was no suggestion that a referral was made to Adult Safeguarding, or Children’s Services or MARAC. No s.184 notification was issued, and no advice was given to Ellie about how to pursue legal appeal.

Over the next two months Ellie approached the Council three more times before a homeless application was accepted upon the advice of one of our caseworkers, and even when it was Ellie was still not accommodated, despite the automatic duty to do so. Ellie was not actually accommodated by the council until after the birth of her son. Ellie also stated that the officer she initially dealt with was rude and abrupt throughout her contact.

Action by JustUs: One of our caseworkers supported Ellie to complain and we understand she received an apology and £500 compensation for the injustice she suffered.

Comment: The failures that led to Ellie being left homeless were down to the fact that her approaches for assistance were not recognised as homeless applications as they legally should have. This meant that no inquiries were conducted, and no written decision was issued, which, among other things, would have informed Ellie how to get the support she needed. Ellie’s perception of the lack of sympathy from officers and the pressure placed on her to make a decision about the refuge are also completely at odds with the Law and Guidance.

Ann

Ann fled her husband’s home following several instances of physical abuse. She entered another relationship and became pregnant. She still lived in Bedford at this point and was scared that her estranged husband would attack her if he became aware she was pregnant. She left her home in Bedford to return to her family home in London, but the relationship broke down with her family due to the circumstances around her pregnancy. She stayed with some friends in Council B’s area. She approached Council B several times and it failed to fulfil various duties, which the LGO subsequently upheld and recommended that Council B pay her compensation. Instead of housing her, Council B arranged for her to be transported back to Bedford, despite Ann repeatedly saying she and her unborn baby were at risk of being attacked by her husband.

Ann presented to Bedford Borough Council, who refused to consider housing her out of area, despite Supplementary Guidance clearly saying it should have been considered (para 55). Whilst Bedford Borough Council repeatedly recorded Ann’s reasonable beliefs about the risk of violence to her, officers never completed any kind of risk assessment or made any record of having considered the issue. Instead it advised her to withdraw her homeless application and approach Council C, declining to tell her that she did not need to withdraw her application to Bedford. Again, no MARAC referral or Children’s Services referral was considered, even though this would have meant some kind of formal risk assessment taking place.

Ann approached Council C three times, but each time was bounced back to Bedford. Council C subsequently admitted fault at the first available opportunity and financially compensated her for the injustice its failures had caused her.

Ann lost hope in ever getting any assistance so stayed with an acquaintance for two weeks before re-approaching Bedford Borough Council. She was temporarily housed in Bedford Borough, despite her making it clear she felt unsafe and eventually housed her in Bedford town, but in unfurnished accommodation where she did not even have access to a bed until one of our case workers arranged for one to be delivered.

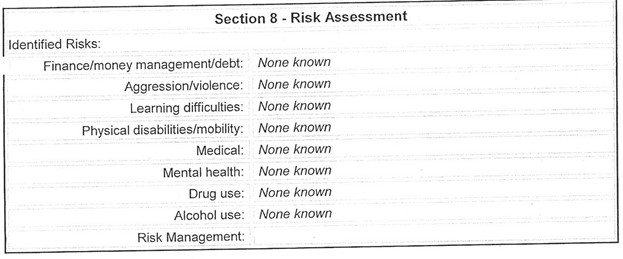

Action by JustUs: Having obtained a bed for Ann’s accommodation we subsequently complained to Bedford Borough Council, the main substance being that she should have been housed out of the district due to the risk she was at in Bedford – ‘Councils should generally provide accommodation in their own district unless there are clear benefits in housing an applicant outside the district like there being a risk of violence within the district’ (para 55 of Supplementary Guidance). Initially the Council strongly denied that there was any risk to her, but then inadvertently acknowledged they did believe she was at some risk later during the complaint process. The other substantial element of the complaint was that no risk assessment was ever completed. The closest Housing Options’ procedures comes to a risk assessment of domestic abuse was this one, which is taken from Ann’s records:

Figure 1: Risk Assessment from Ann’s records

Figure 1 shows that it was never completed although Ann’s records repeatedly referred to the risk throughout the Council’s notes and there was no other trace of the risk being considered elsewhere. Bedford Borough Council never accepted that they should have done more to assess the risk to Ann and the LGO did not comment on the issue either, we believe because it is out of their scope of inquiries. The second stage complaint stated that the Council does not have its own policy regarding domestic abuse as it is legally required to.

One further concern which arose from Ann’s case was the fact that Senior Bedford Borough Staff stated openly in one of the complaint responses that Council C is well known for the illegal practice of gatekeeping, but at the same time seemed unwilling to acknowledge any significant shortcomings in their own practice, despite several upheld complaints against them.

Comment: Ann became an unwilling victim of three local authorities passing her from pillar to post, when all three had a duty to help her. Additionally, Bedford Borough Council produced no evidence that the risk of abuse to Ann had been considered, although the existence of risk was eventually acknowledged. As a result, Ann had her baby having just got through a highly distressing period which was exacerbated by these Council failures.

Becky

Becky originated from Bedford but fled domestic abuse several years before 2014. She lived in a women’s refuge on the south coast before settling down there. As so often happens in cases of domestic abuse, the perpetrator found her and moved in with her and the abuse recommenced. The local police in that area had attended numerous instances of further physical abuse. After a particularly nasty instance of physical abuse, Becky fled her home and returned to Bedford. She was helped by her extended family as they tried to rally around her. She had been diagnosed with depression and felt she was at risk of relapse into intravenous heroin use (a factor recognised in homelessness case law to lead to vulnerability). She attended the local substance use service in Bedford and was supported to approach the Council to make a homeless application.

After two approaches the Council had not accepted a homeless application, but had offered her a place in a refuge in St Albans, showing that they understood her to be at risk of domestic abuse. The Refuge placement did not qualify as a legitimate discharge of the Council’s duties, even when ignoring its location. She declined this due to her new job and family support network in Bedford. The Council maintained that she had explicitly declined to have her approach accepted as a homeless application on the first two approaches, we maintained that she had not been given anywhere near enough information to make an informed decision about it – she would lose nothing by doing so and could easily be housed as a result, so we could see no rational reason as to why she would expressly refuse the assistance available. No safeguarding alert was made, nor was a MARAC referral offered to Becky, even though the information she had already provided suggested a high enough score to warrant a referral.

Action by JustUs: After some correspondence with Housing Options we advised Becky to return to Housing Options again. She did this, but again no homeless application was accepted. Instead, a room in a shared house occupied by four unknown males was offered to her, which was not a legal discharge of any duties. She said did not feel safe to accept it and would not have any right of review of its suitability as it was not part of a legal discharge of the Council’s duty.

We then supported Becky to complain, which in itself constituted another homeless application. The Council then made inquiries of another police force (without having Becky’s consent to share any of her data with them) before a homeless application was accepted, which again is unlawful. After more toing and froing, a homeless application was finally accepted and the Council said that they made a decision the same day, although the postage mark on the decision envelope showed it had not actually been sent out until a week later. The initial decision was that she was non-priority need, although no inquiries had been made to her GP regarding her mental health issues or the substance use service about her risk of relapse in substance use, both of which would have been legally relevant to the level of harm she was at risk to. We requested a review for this decision but before this was completed the Council accommodated her in Rent Deposit Scheme accommodation, meaning the decision could not be reviewed.

We supported Becky to progress through the complaints process and on to the LGO. The LGO found maladministration as the Council had not accepted a homeless application when it should have and that the decision notification was not issued when the Council says it was, but because Becky was accommodated before the review ran its course the veracity of the non-priority decision could not be looked at. This meant it could not find significant injustice, even though Becky was homeless for 16 weeks before the s.184 decision was reached, and she had not been accommodated pending inquiries during this period.

Comment: Becky’s case is a good example of how difficult it can be to get an approach for assistance acknowledged as a homeless application without an experienced professional repeatedly insisting that it is. It is also a good example of how getting the response to cases of abuse wrong can lead to victims being vulnerable to further abuse.

Laura

Laura had been homeless on and off for many years. She informed the Council that she had been living with her abusive partner but couldn’t take it anymore. Laura has a learning disability, ongoing severe self-harm issues, many years spent in care when she was a child, substance use and a long history of sexual abuse from early childhood.

Action by JustUs: Laura made the Council aware of these issues when we accompanied her to make a homeless application. The Council placed her in temporary accommodation immediately but made no effort to report the abuse she had made the officer aware of to the adult safeguarding team.

We subsequently made an adult safeguarding referral after further abuse and the Safeguarding Team took various actions to manage the risk, including making a referral to the Mental Health Team.

The Homelessness Code of Guidance states that a s.184 decision should be issued within 33 days of the application in most cases, unless there are exceptional circumstances causing delay. In Laura’s case the decision took 69 working days, although there was no reason why it should have taken so long (the information from Laura’s GP took only 20 working days after the inquiries started). A s.202 review should be completed within 8 weeks. Upon requesting a review of the non-priority decision, 7 weeks into the 8-week period, Bedford Borough Council passed the review on to a private company to conduct on its behalf. It is, at the time of writing, 22 weeks since the review was requested and has still not resulted in a decision.

Comment: The delays that Laura experienced were highly distressing for her and meant that she was unable to start the process of rebuilding whilst the uncertainty was hanging over her. The failure to inform the Safeguarding Team of the abuse also delayed a more robust offer of support being available to her. There is no obvious reason for these delays and it costs the Council much more in terms of temporary accommodation costs.

Update [not submitted in original report] Laura was initially told that she was not vulnerable so did not qualify for statutory assistance because she was not in priority need. JustUs challenged this decision and it was overturned. Laura was also told that she had made herself intentionally homeless, which again JustUs challenged and it was overturned, meaning there was a full duty for the Council to house her in settled accommodation. She moved in a few months later. Whilst accompanying her to buy items for her new home, Laura explained to the caseworkers that it was the first time in her life she had ever got to choose her own bedding.

Natalie

Natalie left her husband following numerous incidents of abuse. She subsequently started a relationship with someone else and moved in with him. She was then subject to abuse in the new relationship. On one occasion an assault left her with brain damage for which she was admitted to hospital. She discharged herself against medical advice as she felt too anxious to remain in the hospital. She had nowhere to live so sofa-surfed and slept rough some nights.

A few weeks later she approached the Council and a homeless application was not accepted.

Action by JustUs: Natalie was referred to JustUs the next day by another agency and we accompanied her to Housing Options again. She was initially told that she would need to provide medical evidence of brain damage before an application would be accepted, and then when we explained that this was not legal, the officer said she would make some inquiries of the GP before deciding whether to accept an application, which we explained was not legal either. The officer did not let our caseworker speak to a manager so he emailed senior staff outlining the situation, including the information about the brain damage and the fact that Natalie was prescribed anti-psychotic medication only used to treat non-psychotic anxiety in extreme cases. This should have been enough information to cross the s.188 threshold to accommodate pending inquiries but a same-day non-priority decision was made, even though her GP was contacted but the officer proceeded with the decision before a response was received.

Following this the caseworker received an unpleasant email from a senior manager at Housing Options. It attacked, without any clear basis, the rationale for insisting that a homeless application was accepted and stated that doing so was a waste of Natalie’s time, even though the caseworker was simply insisting her approach was recognised as it legally should be. We subsequently advised Natalie to see her GP to get more evidence about her medical history. At this appointment, she was diagnosed with PTSD, her brain damage was documented, she was signed off from work for 3 months and she was prescribed additional anti-anxiolytic medication. With this information, we supported Natalie to re-approach the Council and she was accommodated pending inquiries. She moved into accommodation from the temporary accommodation a few weeks later.

Comment: It should have been apparent to Housing Options staff that an individual who had been brutally attacked by her partner 6 weeks before resulting in brain damage may have been vulnerable, and it should not have needed concrete medical evidence from her GP to cross this low threshold. Housing Options’ approach to resist accepting homeless applications to people who are actually vulnerable is a complete frustration of the principles of the Housing Act that were set out to protect them, and its failure to report abuse as it should mean opportunities to minimise abuse is often missed.

Update August 2017: The first stage complaint was issued by one of the officers involved in the original decision and the complaint was not upheld. However, the second stage complaint upheld the issues relating to the second approach for assistance, and the senior manager who issued the response acknowledged that Natalie was ‘clearly very vulnerable’. The Council apologised and awarded compensation as the senior manager acknowledged that Natalie had been left homeless as a result of the Council’s failures.

Emma

Emma was a lady in her early twenties. She had been raped in her mid-teens and diagnosed with PTSD, for which she was still medicated with benzodiazepines, and on which she had become physically dependent. In February 2015, her Recovery Practitioner at Can Partnership wrote to Bedford Borough Council giving her medical and social history, explaining that she had been sexually exploited by her family from childhood. It also stated that she was still living with her parents and reported ongoing extreme psychological and physical abuse as well as grooming for sexual abuse, resulting in worsening mental health issues and suicidal ideation.

Action by JustUs: Legally, the information provided in the letter by her Recovery Practitioner, crossed the threshold for s.184 inquiries to take place and a written decision to be issued, but it appears no s.184 notification was issued and Emma was left in her abusive home. She was referred to JustUs six months later. JustUs accompanied Emma to Housing Options where the s.188 duty was fulfilled, and Emma was accommodated immediately. Emma was supported by the Council into private accommodation a few weeks later, before the s.184 inquiries were completed, but it seems highly likely that had the inquiries been completed Emma would have been considered more vulnerable than an ordinary person would be due to her mental health diagnoses, benzodiazepine dependency initiated as part of her medical treatment (and thus in itself constituting a disability under the Equality Act 2010) and the nature of the domestic abuse that she experienced from her parents, meaning there would have been a duty to house her anyway. Rent Deposit Scheme tenancies are used in this way as they have favourable implications for the Council’s performance indicators – the intervention is classed as a homelessness prevention and the person is never recorded as being homeless, decreasing the number of homeless people recorded by the Council.

Comment: Again, the Council did not issue a s.184 notification or make a safeguarding or MARAC referral despite the abuse reported by Emma being ongoing at the time of the application and the fact that Emma had clear care and support needs.

Section B: Conclusions

The recurring issues from these case studies are that:

Section C: Recommendations

The case studies clearly demonstrate that the failings experienced by each individual were not isolated. Bedford Borough Council has an opportunity to improve its services to homeless people fleeing domestic abuse so that abuse can be identified and responded to properly so that further abuse is minimised. This will bring immediate savings from related services and long-term savings as victims are given a realistic chance to leave abusive relationships and rebuild their lives.

Section D: Background summary of relevant legal and policy requirements

Homelessness Legislation: Housing Act 1996 and the Department of Communities and Local Government’s Homelessness Code of Guidance

The Department of Communities and Local Government’s Homelessness Supplementary Guidance on Domestic Abuse

As stated above, Councils must have regard to this guidance and failing to do so in a way that causes significant justice can result in that person being financially compensated:

The Care Act 2014

The Care Act 2014 came into effect on the 1st April 2015. It places duties on councils in regards to reporting and investigate alleged abuse or self-neglect of adults who the Council have reason to suspect have any care and support needs, including relatively low-level needs (s.42 of the Act and 1.3.2 of Bedford Borough Council’s Multi-Agency Adult Safeguarding Policy, Practice and Procedures 2016), even if that person has not been previously assessed as having any care and support needs. The Safeguarding policy also relates to those ‘who may or may not be eligible for community care services whose needs in relation to Safeguarding is for access to mainstream services and the police, or who are unable to protect themselves’ (1.3.2).

Bedford Borough Council’s Multi-Agency Adult Safeguarding Policy, Practice and Procedures 2016

Domestic Abuse Policy

In terms of domestic abuse policy, we requested the Council’s own policy but did not receive it. When we approached the Council again, we were informed by the Assistant Director of Commissioning and Business Support that:

'In relation to your request for a copy of the Council’s Domestic Violence Policy, this is available on the Council’s website http://www.bedsdv.org.uk/ I would point out that there is no requirement on the Council to have a Housing specific Domestic Violence Policy but that the policy referred to in paragraph 29 of the Code of Guidance is the overall Domestic Violence Policy held by the Council.

The quoted link does not lead to any such policy, so it does not appear that this response is in line with the requirement of the Supplementary Guidance on Domestic Abuse that ‘Councils should have strong policies to identify and respond to domestic abuse’. When we contacted Central Bedfordshire Council who co-ordinate the policy for Bedford Borough Council we were told that there was no policy but were instead signposted to a website, ‘Safelives.org.uk’ (copies of email correspondence available if necessary). We also made an FOI request for the Council’s Domestic Abuse policy and received a policy that relates to Council staff experiencing domestic abuse but did not receive any policy relating to clients experiencing domestic abuse, which we found surprising given that it seems probable that Council officers from many departments will have contact with people experiencing domestic abuse. It therefore appears that the Council does not have a Domestic Abuse policy.

However, the Safelives website that we were signposted to by Bedfordshire Domestic Abuse Partnership published a number of reports about domestic abuse. One report, Getting it Right First Time stated that:

Child Safeguarding

The Children’s Act 1989 and HM Government’s Working Together to Safeguard Children 2015 guidance follows near-identical principle of immediately referring any concerns about any child to Children’s Social Services.

Freedom of Information Requests

JustUs requested one set of Freedom of Information requests in 2015.We asked how many people in 2014 approached the Housing Options service for assistance as homeless people (thus triggering the s.184 duty to make inquiries and issue a written decision). The Council gave figures for two separate 10-day periods which, when extrapolated, would suggest that around 800 homeless households approach the Housing Options Service for assistance each year but only around 400 are treated lawfully in terms of inquiries and written decisions being issued. It is a recurring theme within the case studies below that people triggered the duty to make inquiries (and to accommodate pending the outcome) but were not treated as such, leading to significant injustice in some cases. It took around 6 months to obtain any figures (requiring JustUs caseworkers to use to complaints policy to prompt the formal response).

JustUs made one FOI request in 2016, asking how many homeless households approached the Council in 2015 whilst fleeing domestic abuse, and how many referrals were made to Adult Safeguarding, Children’s Services and MARAC.

A further breakdown of the figures was also requested, but the Council did not provide these figures as it said it would have taken disproportionate effort. The legal duty to advise us how to refine the question to elicit at least some relevant information was not fulfilled, but this may be a course of action open to Mr Yasin in response to this report.

The figures obtained showed that:

Without the further breakdown of the figures requested, it is not possible to draw as many definite conclusions as we would have liked, but we believe it highly improbable that a service dealing with many vulnerable often reporting some level of abuse (whether domestic abuse, financial abuse from a landlord etc.) did not have one instance that warranted a referral being made to Adult Safeguarding. Similarly, it seems that 4 referrals to MARAC seems improbably low. The figure of 93 referrals to Children’s Services will include families not experiencing domestic abuse, so more detail on these figures would be needed to draw any conclusions, specifically how many of the 135 households fleeing abuse included children, and how many of these were referred to Children’s Services.

These figures from the 2015 and 2016 clearly corroborate the concerns we have in relations to the individual cases we have worked on. The fact that 400 people were recorded as being turned away in 2014 (which would have included several of our clients whose complaints were upheld for this reason) is hugely concerning, as is the fact that zero adult safeguarding referrals were made and only four MARAC referrals were made in 2015. This should be all the more surprising when HM Government reports have noted the strong relationship between homelessness and abuse (e.g. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/homelessness-applying-all-our-health/homelessness-applying-all-our-health )

Following the first FOI request and complaints we raised about Housing Options’ practice, Housing Options amended their procedure to include a person’s decision to not make a homeless application following their approach. However, this seems to be a ethically questionable way of dealing with the issue of following s.184 lawfully – in our clients’ experience since this change was introduced they have not been told what a homeless application actually is and are being told that there would be no duty to them and that it would be a waste of time. Several of our clients have been advised against making a homeless application but have been supported by us to re-approach and be found to be vulnerable. This should be impossible if the Council officers were carrying out their duties diligently.

Data Protection Law

The seventh principle of the Data Protection Act 1998 states that Bedford Borough Council, as a data controller, must take ‘appropriate technical and organisational measures shall be taken against unauthorised or unlawful processing of personal data and against accidental loss or destruction of, or damage to, personal data.’ This would mean that discussing sensitive personal data with homeless clients in an open plan customer service centre is not legal as it would be easy for members of the public of other Council employees to overhear sensitive personal data being discussed.